Introduction

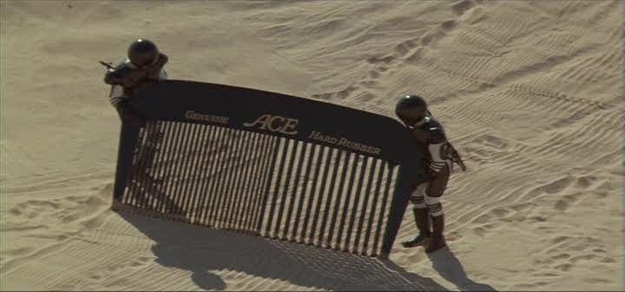

Am I going to match? This is the question that medical students going into their 4th year ask themselves over and over, poring over every detail of themselves and their application with a fine tooth comb. Or in some cases, the big comb from Spaceballs.

This post began in an airport in Lansing, Michigan (yes, who knew they had an airport? Definitely not me until a month ago). It currently the tail end of interview season for 4th year medical students as we scurry about answering questions (and asking more questions than we get asked, hilariously enough) and figuring out where we want to spend the next 3-7 years of our lives. While I will hopefully shed light on the match process for those non-medical folks out there (see: sorority match with a lot more traveling and slightly less cheering involved), this post is for the medical students, especially those who find themselves in their third or fourth year.

I’m going to do something that I wish I had seen as a rising fourth year student without having to go to probably the worst site on the Internet: Student-Doctor Network. I think the worst parts of Reddit and 4chan are better than SDN, and believe me, I’ve seen the kind of depraved things the Internet can do. The reason being SDN cultivates anxiety, anonymity, and everyone claiming 260+ scores on STEP 1, 20 first-author publications, and other things that make the average, below-average, and even above-average residency candidates develop hyperhidrosis (a profuse sweating disorder). And even if these people aren’t in the astronomically high ranges of scores, there are more 240’s and 250’s claimed on SDN than 220’s, even though the average sits around 230. I am a real person with a real name that isn’t “HarvardMed1991” with a 275 board score. This is obviously hyperbole, but sometimes isn’t that far from the truth. I am numerically somewhere near or below the “average medical student” applying to a decently competitive specialty: general surgery.

This post is part 1 of a 3 part series. This post will include a breakdown of statistics on the match to get the most accurate answer to “What are my chances of matching?“. Additionally, this post will highlight the important numbers behind the Match, go into what factors are important getting selected for interviews, and show what is important (and more importantly, what is not important) to consider in shaping your interview process and medical school career.

This post was initially going to give the entirety of my ERAS application, but I’ve decided to save that for part 2. Part 2 will include my ERAS application, complete with transcript, board scores, rotation comments, my personal statement, and more. Then, more importantly, I am going to give you the list of places I applied to and whether or not I got an interview at that place. PART 2 IS NOW POSTED HERE! Part 3 will occur when match day comes, where I will I break down my interview trail by institution, how I felt at that place, and what I thought was a running rank list at the time. I’ll compare that to my final rank list. If there is a fourth part (which is likely), it will be my tips and tricks for the interview trail, from finding hotels to what to wear to the night before event. Also, I will go into the match algorithm at that time, as it is relatively simple but crucial to making sure you understand how to make your list correctly (foreshadowing: you can’t game the system, and it’s made to favor us, not the programs).

There are multiple reasons I’m doing this, but the rationale for part 1 is because there’s so much data that the NRMP puts out on the Match that the key points are hard to find. The answers to the biggest questions medical students want to know are buried within 300+ pages of reports. I am a mathematician by trade (in so much as my undergraduate degree was in math), and one of the things I enjoy is making sense of a large amount of data and selecting the most important trends and/or facts. Data can easily be misunderstood or misinterpreted, and while I’m not perfect, I think I have enough background to give a reasonable interpretation for the average medical student who doesn’t want to spend hours sifting through the NRMP data.

My story, a surgery applicant

The reason for me releasing my ERAS application in part 2 is because despite all of the data, what we value are often personal anecdotes. I can tell you that plastic surgery applicants with 14 interviews match >95% of the time, but the story I heard on the interview trail of a plastics applicant from 2016 not matching with 14 interviews hits much harder than that statistic. I am one data point in a sea of over a thousand general surgery applicants, but seeing “hey that guy only had x research papers or this STEP 1 score and still got these interviews” might put you at ease more than numbers. Also, you can compare yourself to me, especially if you’re a surgery applicant, and judge if you’re more or less competitive and perhaps adjust accordingly. Part 3 will be to see the trail through my eyes and how it will be different from how you view it.

Medical students are notorious for being hyper-critical and preoccupied with comparing themselves to their colleagues, especially those going into the same specialty. I had a lot of anxiety about the process and my chances of matching, and it was difficult to tell how well-founded those fears were. By board score and class rank, I am considered below-average for general surgery in nearly every category, as found on the NBME’s residency match data. Therefore, I applied to 58 programs, which is 16 more than the average number of programs applied to in surgery for those that matched in 2016.

My main point is that my fears ended up being unfounded, as I received 18 interview invitations. In hindsight I probably applied to too many programs, but a lot of good that does anyone. I’ll save more of my theories about my process particularly in Part 2 PART 2 POSTED HERE, but I wanted to at least include a little bit about me.

Sources = cited

Alright, it’s time to dive into the statistics and numbers behind the match. But first, like any good investigation, let’s go to the sources first. I am not going to copy/paste any of the graphs or figures so that I don’t somehow get destroyed by the copyright police, so I’m going to site each piece of data as I go along.

I’d recommend everyone reads this, as it is the press release for the 2016 NRMP Match. I’d say reading this is a good overview of the match. Most of the following reports are found here on the parent page: Main Residency Match Data

- NRMP Main Residency Match Results 2016 – This is the PDF that contains the bulk of information I break down. It includes the overall data including number of applicants to a specialty, how many matched, etc. It is broken down by type of applicant. By type I mean either U.S. allopathic seniors, D.O. applicants, and both U.S. and non-U.S. international medical graduates.

- Charting Outcomes in the Match for U.S. Allopathic Seniors – This breaks down each specialty by USMLE scores, number of work/research projects/volunteer activities, and other factors for U.S. Allopathic seniors, as they are the most well-studied group.

- Impact of Length of Rank Order List on the Match – A short document doing exactly what it says – show how many places were ranked by people who did and didn’t match. A note here, a place someone ranks is somewhere they interviewed. You don’t have to rank every program you interview at, but the number is mostly indicative of the number of interviews received.

- Program Director Survey of Important Factors in Selecting and Ranking Applicants – This shows what program directors (and therefore their programs), on average, think are important when both selecting applicants for interview and determing what order they rank them in afterwards.

- Results of the 2015 NRMP Applicant Survey – This is the counterpart to #4 in which applicants give an idea of what they thought was important when they determined how to rank programs

You can have each of these open as you read the following points, as I’ll refer to specific charts and figures in parenthesis after the statements. This will be useful if you’re applying to a specialty other than surgery, as I’m going to use that as most of the examples. I’ll throw in some of the more competitive and less competitive specialties for emphasis at my discretion.

The main points

I’m going to do my best to make this easily digestible, but there are lot of numbers. I will, however, put emphasis on the main point I’m trying to make with the data and make it bold and easy to read. You can search for the point down later in the post if you only want to read about that one topic, each of them stand on their own. Here are the points I am going to make, and the data will be divided in each section below:

- The overall match numbers are brought down by international medical graduates and other groups, who match at much lower rates than U.S. allopathic seniors.

- You are very likely to match if you are a U.S. senior, and match at one of your top choices.

- There are pretty good explanations for most of those that don’t match, and while some are set in stone before the interview process, some are avoidable.

- The raw match rates don’t tell the whole story, and your odds are better than you think.

- Couples are confounders.

- Step 1 isn’t the be-all, end-all, but it is single most important number in your application.

- Once you get an interview, the factors that influence how high the program ranks you shift from those that got you the interview in the first place.

- So many parts of your CV and application don’t carry much weight, and in fact do not have increasing utility for greater numbers of experiences.

- A survey of what was important to applicants is available, and in general, more interview offers are better.

First off, to those of you who don’t know why anxiety exists as to matching for residency: the number of residency positions is much smaller than number of applicants, as 42,370 people apply for 27,860 PGY-1 (first year) positions. Doing the math, that means roughly 66% of applicants can match. For the purposes of my argument, and since the spots mostly fill up every year (1,178 were unfilled, 607 were PGY-1 only preliminary** spots in a few specialties), I am going to assume that this means that 66% of applicants do match (even though the reality is slightly lower since some people choose to not try and fill those random other positions). So, here’s our starting point: 66% of applicants match. Let that anxiety sink in for a minute before I obliterate it.

**Quick note: Preliminary (known as “prelim”) positions are those that are slated only for 1 year and do not carry a guaranteed ticket to continuing through residency. These people often apply during their prelim year for what are called “categorical” spots, aka the “5 years of surgery training” spots that fully certify you as a practicing surgeon. These prelim spots exist in a few specialties, but they are more common in general surgery than most other specialties. Generally, these are what less-competitive applicants resort to in order to prove that they can do surgical residency. This is because they actually are an intern for a year. Often, there were doubts from their application that they’d be able to be a good surgery resident for one reason or another. I’m not sure the numbers on how many match after a prelim year in surgery, as I don’t know if that specific data exists. This excerpt was only to shed light on what a prelim is.

Point #1: The overall match numbers are brought down by international medical graduates and other groups, who match at much lower rates than U.S. allopathic seniors.

Let’s break down that 42,370 number. Turns out, that includes 3,099 who withdrew from the match and 3,795 who did make a rank list for whatever reason, either due to not getting any interviews or deciding to not make one (Source 1, Table 4). This means that there were actually 35,476 active applicants, which means that 78.5% of applicants match. Simply having 1 or more programs on your rank list and going through the match already increases that initial match rate. Cool, huh? Let’s go deeper.

The overall match rate is brought down mainly by a large number of Non U.S. citizen international medical school graduates. 10,170 of them applied, about 2,600 withdrew/did not have a rank list, and 50.5% of 7460 active applicants matched. U.S. citizens who graduated from international medical schools had 7,364 students apply, about 2100 withdrew/did not have a rank list, and 53.9% of the 5,323 active applicants matched (Source 1, table 4, pg. 15) The other groups that are small include previous graduates of medical schools (i.e. those that apply after a prelim or research year), Canadian graduates, and fifth pathway programs (a path by which foreign medical grads can enter into US residency selection).

If you take out these groups, then you are left with a two groups: U.S. allopathic seniors (M.D.’s) and U.S. osteopathic seniors (D.O.’s). U.S. allopathic seniors make up the bulk of residency applicants, and they are who I will focus on in my examples. This is because not only are they the largest group, they are the most well-studied. I also happen to be one of them, and most of the people I interact with are U.S. allopathic seniors. This is not to disparage other groups, but it is to use the majority to illustrate my points, which can then be applied to the other groups. If you happen to be in one of these groups, you can apply it to figure out the match rates specific to you. The information on rank lists and on what programs find important is crucial for everyone.

So, what’s it like for U.S. allopathic seniors?

Point #2: You are very likely to match if you are a U.S. senior, and match at one of your top choices.

93.8% of 18,187 U.S. Allopathic seniors matched (Source 1, pg. 1). Woah, that looks a lot better already, doesn’t it?

You can find the match rates of U.S. osteopathic senior students hovers near 80%, which is still quite high. It should be noted that their match rates into more competitive specialties, such as the surgical specialties, are comparatively lower than their allopathic counterparts. Often, less apply to more competitive specialties relative to allopathic graduates. That does not mean matching into these areas is not possible for osteopathic graduates, just less likely.

So, now that almost 94% match, let’s see how well they matched. To measure this, let’s see how high on their rank list they matched. There’s a handy pie chart that shows of those U.S. seniors who matched, 53.0 % matched at their first choice, and 79.2% matched within their top 3 choices (Source 1, Figure 7). That’s exciting! An 80% chance of being at your top 3 programs is a pretty good. The data carries out to the 4th match including another 6% of applicants. That means 14% match outside of their top 4, and this is where they stop including data for each rank.

So, not only do you have a great chance of matching, you have a great chance of matching at one of your top programs! But, there’s the 6% that’s the looming number: those who don’t match. That 6% is much more scary than the 94% is reassuring, so I think it deserves some time. Let’s dive into that after this quick interlude.

A note about U.S. students at international medical schools: Moral of the story, as a 4th year student at a United States medical school, you are likely going to be okay. If you’re from an international medical school (i.e. the Caribbean), you have the odds stacked against you more than U.S. seniors. I’d dare say there are many reasons for the lower match rate, but the school itself isn’t necessarily causative. Students who don’t get into US schools are generally not as strong of students (or had some red flags on their application or in their interview), will therefore most likely tend to not do as well on board exams, and might have some of those red flags persist when applying to residency.* Again, this isn’t the majority (as 53.9% of these people matched), and those statements don’t apply to everyone, but in general I think those are a few of the reasons. It’s like wondering why Ivy League undergraduate schools have such successful graduates: sure, it has something to do with the school, but I suspect having high quality students before they even set foot on a college campus has a lot to do with it.

*This is one of those “behind the numbers” sort of ideas that seek to explain why a statistic is a certain way. Asking the “why” of a number is important, because there are likely underlying reasons for the match rate of U.S. students at international medical schools being a little over half that of U.S. seniors. Correlation with going to an international medical school does not imply or necessitate causation that their medical school was the source of their lower match rate. Being aware of confounding or other variables is an important concept in scrutinizing a statistic or research idea.

Point #3: There are pretty good explanations for most of those that don’t match, and while some are set in stone before the interview process, some are avoidable.

Let’s get back to this number: 6.2% of U.S. allopathic seniors did not match.

That means 6/100 United States senior medical students who start off the process do not match. Groundbreaking math, I know. But that number is terrifying. Statistically speaking, you are much more likely to not be in this group. You are nearly fifteen times more likely to match than not match. That’s good news. But here’s the question: Why do these students not match?

I’m going to offer a few explanations here. They basically boil down to 4 categories of people: the struggling, the unrealistic (some might call this the risky), the impersonal, and the disasters.

The struggling. These are the…not so great students, at least on paper. They have problems with failing courses or board exams in medical school. About 5% of U.S.Canadian MD students fail USMLE STEP 1, about 5% fail STEP 2, and on NBME exams about 5% of students fail (Source, select 2015 and the appropriate exam).*** I’m going to go out on a limb and say that it is likely the group that fails STEP exams, the group that fails NBME board exams, and the 6.3% that don’t match have significant overlap. There’s no data to support this in the NRMP provided materials that I am aware of, but I think it’d be interesting to know. Therefore, if you passed your clerkships, passed your shelf exams, and passed the STEP exams, you are very likely not going to be in this 6.3%.

***While we’re going on about exam statistics, 22% of students at international medical schools fail STEP 1, which lends towards my hypothesis earlier about those students not being as strong even before they got to medical school, or that their medical school doesn’t prepare them as well.

The unrealistic. Those that never failed a STEP exam, clerkship, or class (and even those that did) are likely in a part of that 6.2% that were not realistic with their expectations. I’ll be frank, if someone has a 210 on STEP 1 with no research and applies to orthopedic surgery, they likely will not match. If an applicant only applies to top programs in general surgery (or any specialty) instead of a broad range even though they have a 250, they decrease their chance of matching. Gambling only on top programs, who get so many phenomenal applicants that at some point I swear getting an interview sometimes comes down to luck, is dangerous.

If they only apply to 10 programs, they are sabotaging themselves and will be less likely to match. 42 is the median number of programs applied to by U.S. Seniors that matched into surgery (Source 5, figure SG-4, pg 172). Casting a broad net is essential to insuring a large number of interviews. The average number of programs ranked for all U.S. seniors combined is 11.97 for those that match (Source 3). That means going on 12 interviews gives a fairly good shot of matching across the board. Since most people don’t get interviews from 100% of the places they apply to, applying to more than 12 is a good thing. More is generally better in more competitive specialties like plastic surgery, less is okay in less competitive specialties such as family medicine. The median number for those who did not match is 7.11. Those that get less interviews (because they are weaker candidates) rank less programs and therefore are less likely to match. No surprise there.

The unrealistic are the people who should rethink the specialty they apply to, apply to more programs, or at least be aware that they are taking a long shot. Getting good mentorship, such as meeting with the residency director at your program for your chosen specialty, talking to many faculty and advisers, and being aware of the data is essential to make an informed decision. If people in surgery are telling you to reconsider going into surgery, that’s a huge red flag. Those that are unable to be honest with themselves and realistic with their expectations cross the border from the unrealistic to the delusional (someone who has a fixed false belief). If someone applies to orthopedic surgery with a 210 STEP 1 score and no research, they should be very aware their chances of matching are slim-to-none, and they should consider a different specialty.

The impersonal. These are the students that have the scores, the grades, or the overall academic prowess to get an interview based on their application. They are not struggling or unrealistic. However, they either can’t hold a conversation during their interview, come off as lacking confidence, or straight up can’t play nice with others. Every program has a story of some applicant who seems great, then blows up on the program assistant**** (this is the person who emails everyone and sets up interviews, etc.), and therefore the program doesn’t rank them. The impersonal people blow it at the interview stage. They might be somewhat rare, but they exist. The fact that there are multiple people every year with >250 USMLE scores who don’t match attest to this. These people could also have a red flag in their application that isn’t grade-related, such as cheating, plagiarism, or large professionalism issues.

****Hint: that is the person you want to be the nicest to out of the entire program. They aren’t a doctor, but if you rub them the wrong way, that can bomb an otherwise fantastic interview day. They do a lot of hard work, and will be a crucial part of your life as a resident there.

The disasters. These are the people that I nor anyone else can account for. These are the students who are personable enough, don’t have any obvious red flags about them, have the right scores, apply to a realistic specialty, have interpersonal skills and…. don’t get the number of interviews they should. Or they do get a decent number of interviews and…don’t match. I suspect that there are an incredibly small number of them with relation to the other three types I’ve listed above, but I do believe they exist. These things are simply unable to be explained on a large-scale basis, and might be nigh impossible to explain on an individual basis as well. The only explanation I can offer (which I think is both weak on evidence and a probably a small percentage of the disasters) is that the people like this you hear about have something bad in their application that they are either not disclosing or are not fully aware of. Most of us do waive our right to see our recommendation letters, after all.

So, there you have it when it comes to reasons for not matching. Those are the explanations I have for the types of people who don’t match and the circumstances that lead to that.

Point #4: The raw match rates don’t tell the whole story, and your odds are better than you think.

This has been a recurring theme throughout my post, as I tend towards seeing the bright side. There is one piece of data that I want to use to illustrate this point, and it has to do with the number of programs applied to. See, some people apply to more than one specialty for residency. These are often those in competitive specialties. For example, it is common for those primarily applying to subspecialty surgical fields, such as plastic surgery or urology, to also apply to general surgery. This is also somewhat common for those applying to general surgery, who might apply to a medical specialty as a backup, or medicine specialties.

The main assumption I make here, which I think is fairly valid, is that those who apply to multiple specialties do so because of decreased confidence they will match into their first choice. It seems fair: if you are skeptical that you will match into plastic surgery, you also apply to general surgery since you can do a plastics fellowship later. Let’s take a look at general surgery: 1,241 categorical surgery spots exist. There were 2,345 total applicants, 1300 of which were U.S. seniors. 948 of these seniors matched, giving a 72.9% match rate. That means the non U.S. seniors had a 33.6% match rate. Those are both below the averages for overall applicants.

However, let’s look at the number of seniors that listed general surgery as their “only choice” – 791 (Source 1, Table 14). 713 out of these 791 matched, which is 90%. Those that had better applications and therefore were confident enough to only apply to general surgery had a higher match rate. Those that think, “Ehh, maybe I should apply to another specialty” are probably right in thinking that, since they are less likely to match. Again, the 17% boost in match rate is likely due to strength of application, not simply blind confidence to only apply to one specialty. Again, correlation does not imply causation. Of note, there are 1.1 categorical positions in general surgery per U.S. senior, so a 100% match rate would not even be possible. Also related is that 290 U.S. seniors listed surgery as their “first choice” (they applied to more than one specialty) and 219 as their “not first choice” (general surgery was a backup for them). Both had lower match rates than the “only choice” group.

Other specialties show similar trends when you narrow it down to the “only choice” category: their match rate sharply increases. To compare to other specialties for “only choice” with U.S. seniors, 3240/3290 matched into internal medicine, a 98.4% match rate, 99.2% of those that only applied to anesthesia, and 80.2% of those that only applied to neurosurgery matched (also found in Table 14). These numbers not only show how different some specialties are, but that U.S. seniors going into specialties like internal medicine have even less to worry about IF they are good enough to only apply to medicine. This should be reassuring for those of us that are in that position (I only applied to general surgery), and a reality check for those that are applying to multiple specialties.

Point #5: Couples are confounders

I’m not going to talk about it much, but I did want to mention it in case this is your situation: couples do not have nearly as robust data, mostly because they are lumped in with all the other statistics I have sited earlier. It’s impractical to study “couples where one applied to pediatrics and one applied to neurosurgery”, because many such permutations exist. They basically square the number of possibilities that exist in the match. The data I will share is that of 1,046 couples that applied in 2016 (2,092 individuals), 971 matched (95.7% match rate), 61 had one of the couple match but not the other, and 14 had neither one match. Those 14 couples must have had a really rough time.

Point #6: STEP 1 isn’t the be-all, end-all, but it is the single most important number in your application.

Alright, now we get to talk about the big honking elephant in the room: STEP 1 scores. This is the one number that causes 100% of medical students’ anxiety before the end of their second year. This number also causes anxiety to a large amount of people after they receive their score. “Is my score good enough? It is competitive? Will I get the residency I want?” I am going to be frank with you here, as I stated above: It is the single most important number in your application. The fact is that it is a fairly objective way of comparing two (or two hundred) residency applicants in the midst of a lot of subjective data like letters of recommendation. It is a standardized exam, and is about the only metric that residency programs care about regarding your first two years of medical school.

Notice it does not say it is the most important part of your application.

There is a large amount of data on what STEP 1 score is considered competitive for a particular specialty. I will draw your attention to Source 2, chart 6 (pg. 9), which lists the mean USMLE STEP 1 score of those that matched and did not match into a particular specialty. The small x represents the average score for the specialty, the bars represent the interquartile range, which includes the 25th-75th percentile. This range excludes the top and bottom 25% of applicants so as to not be a messy graph and give the best representation of the averages.

What you can take away from this graph is that specialties such as neurosurgery, dermatology, plastic surgery, etc., are more competitive than pediatrics, family medicine, etc., based on STEP 1 scores. You can find additional data on a per-specialty basis further on in the Charting Outcomes in the Match.

Now that I have been on the interview trail with my 226 STEP 1 score, talked to a bunch of program directors, and looked at further data (which I will mention in a second. Which is an odd saying because it’s not like there are units of time in you reading this. But alas, give me a second), I am going to boil the concept of how STEP 1 applies to the residency program into one sentence: Your STEP 1 score is a barrier for entry, and determines which doors are open and which are closed.

That’s it.

This comes from Source 4, which is a survey of program directors (henceforth known as PD’s) that breaks down what factors they believe are important both for receiving interviews and ranking applicants. This is arguably the most critical source I have provided thus far. It will be the crux of the close of this post, as this is the “real world application” of translating numbers into a spot in residency. Every time a source or paper is presented from a survey, you should always look at how it was conducted, and more importantly, what the response rates are. If only 10% of PD’s responded, this source isn’t likely to be applicable to all residency programs. For those of you that have taken an evidence based medicine course, it is akin to the question “Does this study apply to MY patient?”

In this case, the survey was sent out to 3,599 program directors, which includes every PD across every specialty. There was a 39.9% response rate (general surgery had a 34.7% rate), which honestly is pretty good. I’d say that this is more than a representative sample of PD’s, indicating this can be used as good metric to how all program directors generally think. Another point we have to at least consider that maybe those program directors that responded inherently self-selected for a certain sub-type of program directors.*****

*****This could mean those PD’s that care enough to respond to the survey could be demographically different than those that did not respond. To best illustrate this possible source of bias, imagine a survey sent out to a random sample of men regarding penis size. Those that are on the smaller end of the spectrum might be less likely to respond due to shame or societal pressures, and those on the larger end might be more likely to respond, thus skewing the average. Perhaps more representative of this is if this same study was taken using flyers out in the community asking for men to come in to an office to have their penis measured. That would most certainly result in more men on the larger end of the spectrum volunteer to be studied. Maybe an odd example, but I can guarantee you’re more likely to think of that phenomenon the next time you critically analyze a survey. Sorry, had to nerd out real quick there.

On to the results of this survey. PD’s were asked if they considered a certain factor when offering an interview, and then asked to rate its importance on a scale of 1-5, 5 being the most important. These results were aggregated, and Figure 1 (pg. 3) shows this data succinctly. Here is the main point about selecting applicants to interview regarding STEP 1:

STEP 1 scores were cited by 93% of PD’s (the highest of any factor) and carried a 4.2 average rating, indicating they are important and widely used.

In my talks with program directors, your STEP 1 score functions mostly as a weed-out tool for receiving an interview or not. A lot of programs set a filter for scores below which they will not interview an applicant, effectively tossing their application out before any kind of further review. A frequently quoted number I heard in general surgery was 220 from the range of programs I interviewed at. I wouldn’t hear higher because…I didn’t get above a 230, so I wouldn’t be interviewing at such a place that has a higher cutoff. However, that is anecdotal, let’s take a look at the data collected in this report. For general surgery, it is found in figure GS-3 on page 145.

These show the “Scores below which programs generally do not grant interviews”. These box plots, again, use the interquartile range explained before, so it has the 25-75th percentile. For Surgery, there is a range from 210-220 below which the middle 50% of programs do not offer interviews. There are programs like Johns Hopkins or Harvard which fall above that (I’d venture to say they don’t interview below a 240 or something), or those that fall below (which might interview scores above 200). So, my anecdotal evidence matches up with the data from program directors. Pretty neat.

On the flip side, “Scores above which programs almost always grant interviews” shows that for general surgery, a score above 230 gets your foot in most doors for being offered an interview.

Again, applying this more broadly, your STEP 1 score is a tool for getting interviews in a specific specialty. A 210 will not get you interviews in orthopedic surgery. A 250 keeps pretty much every door open.

Taking this to a personal note: I was pissed about my STEP score (you can read my long post about inadequacy and all of that crap from way back) of 226. But, in hindsight, it didn’t matter if my score was or wasn’t good, it mattered that it was good enough! Your STEP score just needs to be good enough to get interviews. Which leads me to my next point.

Point #7: Once you get an interview, the factors that influence how high the program ranks you shift from those that got you the interview in the first place.

Let’s go again to the Program Director survey, this time looking at the factors that determine how they rank applicants. For those of you that don’t know, programs rank each and every applicant they interview from 1 to x (however many total applicants they interview, minus those that are so bad they are deemed DNR – do not rank). This becomes the program’s rank list that gets transmitted to the NRMP. How high they rank you is found in Figure 2 on page 4. Let’s look at the top 3:

- Interactions with faculty during interview and visit (95% cited, rating 4.8)

- Interpersonal skills (95%, 4.8)

- Interactions with house staff during interview and visit (90%, 4.8)

Notice what is conspicuously absent here? All of the things that were at the top of the list for selecting who to interview! STEP 1 scores fall to 5th place (78%, 4.1 rating), which is quite a drop in the overall importance. Letters of recommendation fall to 6th, and so on. Point here is this: sure, your interview might be heavily weighted towards scores, but once you get to the interview, it is your interpersonal skills, personality, and overall behavior that matters more! They have already determined your scores and grades are good enough to be at their program, so they move on. Residency programs don’t waste time interviewing candidates that don’t have a shot at being one of their residents. Now, this is good news to students who don’t have the highest STEP scores, and bad news to those of us who would rather be caught dead than talking to someone. I think, however, that more people fall into the former than the latter.

To finish this point, I’m going to draw you to the red flags: those bad qualities about an applicant that are rated as being important if found. When it comes to receiving an interview, three things stick out:

- Failed attempts at USMLE/COMLEX (4.6)

- Applicant was flagged with Match violation by the NRMP (4.7)

- Evidence of professionalism and ethics (4.5)

These three things have the highest average rating from program directors, yes, even above STEP 1 scores! Even though they weren’t cited as frequently, this is a big statement. That means that these big red flags will likely tank your application if you have failed an exam or have problems with professionalism or ethics. Remember when I postulated earlier that those people who fail USMLE exams might overlap heavily with those who don’t match? This right here is data supporting my theory.

I’d recommend you go through everything and see what program directors consider important for your chosen specialty. Overall, another interesting point is that only 44% cited research as important and did not rate it very highly. A lot of things like volunteering and all of that are not rated very highly or cited very often. That leads to the next point:

Point #8: So many parts of your CV and application don’t carry much weight, and in fact do not have increasing utility for greater numbers of experiences.

As the program director survey pointed out, there are many things that are ranked fairly low when considering applicants to interview, such as awards or honors in basic sciences, volunteer experiences, and research involvement (Note: that does not mean these things are not important!). Now, these things do change by specialty, but I want to point out a few interesting things regarding surgery in particular.

If we look at the Charting Outcomes in the Match (Source 2), we see in table GS-1 (pg. 73) the mean number of research experiences (3.2), mean number of volunteer experiences (6.8), AOA (17.4%), mean number of programs ranked (12.9) and other characteristics of those that matched, and can see them compared to those that are unmatched. Surprise, those that do not match have lower numbers in just about every category, ranking only 6.5 programs on average (due to less interviews), lower STEP scores, and everything else. Interestingly the only two things in which they have higher numbers are percent who have Ph.D’s or another graduate degree. However, they are relatively insignificant differences, given that 1.5% of 816 with Ph.D’s who matched versus 3% of 149 that did not match is 12 people versus 5 people. Hardly enough to matter. Again, always think big picture when it comes to statistics.

What I want to draw your attention to is not these numbers, but the graphs that follow on pages 78 and onward. For those of you that aren’t following along with the sources, they show some interesting trends. It breaks down how many matched/unmatched for each individual number of research projects, volunteer experiences, etc. Let’s take research as an example, of those who had no research applying to general surgery, 31/43 matched, which is 72%. Those who had 1 project had 92/109 match, 84.4%. Interestingly, those that had 5 or more projects matched at a lower percentage, 238/285 or 83.5%. Granted, that isn’t a very significant decrease, but this trend shows itself in nearly every graph, I’m going to bold it for emphasis:

As far as extracurricular activities go, more experiences generally do NOT give a better rate of match. There is no linear increase with each activity, and frequently those with 5 or more of some experience match at a lower rate. Generally, beyond having 1 experience, there are NO increasing returns for having more.

Granted, these are isolated and taken completely out of the context of an application, but it does generally show that you should spend time on things you care about instead of trying to stuff your CV with a load of crap. In my personal experience on the interview trail, I got asked very little about my small volunteering, occasionally about my 2 small research projects, and got asked nearly 100% of the time about my martial arts training (which is due to a couple of reasons I’ll go into in a later post). Having 10 research, 10 work experiences, and 10 research projects does little good for you. Having one of each that you care about is pretty much all you need. At least generally, this does not necessarily apply to elite institutions. There isn’t per-institution or per-reputation data.

Point #9: A survey of what was important to applicants is available, and in general, more interview offers are better.

Looking at the final source, Source 5: Results of the 2015 NRMP Applicant Survey, is the counterpart to the program director survey mentioned before. It lists what applicants (i.e. medical students) thought were important when it came to selecting programs and how they ranked them. About 50% of U.S. seniors responded. A few highlights are that geographic location, reputation of program, and “perceived goodness of fit” (yes, that’s actually the wording they used) came out on top of factors in choosing where to apply. When it came to rank programs, the interview day experience and quality of residents in program rounded out the top 5 factors. I suggest you look at your specialty of interest.

Taken overall, the median (used in this case to stop those people that apply to 100 program from skewing the mean) number of programs applied to for U.S. Seniors is 30 for those who matched, 54 for those who unmatched. Independent applicants applied to many more programs (75 the median number for those who matched. Woah. Just so you’re aware, applying to a lot of programs gets expensive in an increasing fashion). This is found in Figure 4 on page 9.

Using general surgery, the average number of programs applied to was 42 for those who matched, 51 for those unmatched U.S. Seniors. The numbers were 90 and 80 for independent applicants, respectively. For those who matched, 18 was the median number of interview offers, 13 the number attended, and 13 the number of program ranked. They were 7/7/7 for those who did not match. If you only get 7 interviews in general surgery, your odds are not great. If you got 18, you’ve got good odds.

Wrapping up:

Wow, that turned out so much longer than I expected it to be. It started with a relatively simple idea, and 7,000+ words later and a lot of research, here we are. A lot of times that I write, it’s generally for myself as a way to organize my thoughts and process feelings. This time, it was for you: the first year medical students wondering what lies ahead, the fourth years worried sick about matching, the third years wondering if they have what it takes, the second years losing their minds over STEP 1. This is for you to look at in order to realistically assess yourself, learn a thing or two, and perhaps adjust your life trajectory accordingly.

I hope this wasn’t too dry of a read, as I lost a lot of my usual playful and personal tone at times. I didn’t want to crowd the numbers too much, because I think this is a wealth of important information. I hope that I accomplished what I set out to do: distill an incredibly large body of information into its essence: the important points that those applying to residency should care about.

Feel free to contact me with any questions or points of contention, as it’s very possible I made a mistake that slipped through my editing process. You can leave a comment on this post or message me on Facebook (for those of you that know me). If you want a more personal form of contact, as I’d be happy to give out my email on an individual basis, leave a comment and I’ll find a way to get it to you.

My next post will be me detailing my application in its entirety, as well as the list of places I applied and received interviews at, so look forward to that.

The last thing I’ll leave you with is a saying I heard one of my attending physicians use with a patient, one that I will use in my practice, “I can tell you what will happen to a thousand you’s, but not what will happen to you.” What this means is that it is important to take all the statistics and data into account, but they don’t predict the future for a single person. Remember that.

Good luck, it’s a cold world out there. Best of luck as all the 4th years finish out their interview process, and I’ll leave you with this song to remind you that We Won’t Be Alone in this world, by Feint Ft. Lauren Brehm

-Brandon

Also, if you want more music, this Remix of “Get Schwifty” from Rick and Morty is absolutely ill.

Thanks buddy! Love you for this.

LikeLike

Thanks, glad you liked it!

-Brandon

LikeLike

Thanks for this article! I hope you matched! I can’t wait for Friday to know where I’ll end up; this wait is pure torture…

LikeLike

Luckily I wrote all this last year and I’m currently a PGY1 at St. Louis University. Good luck tomorrow!

LikeLike

Excellent Write-up…You say it all so candidly. Thank you so much. How can I contact you offline?

LikeLike

Just updated my whole website here, there’s now a link near the top of the webpage where you can email me!

LikeLike